We’ve probably all been at the point where we wondered if it would be faster to walk to someone’s house with a flash drive rather than send them a file over the internet. If you haven’t, bear with me, because I sure have. As movies and games grow in size with each resolution or graphics upgrade, while internet speeds don’t always keep up, it’s easy to feel stuck as you watch a loading bar crawl across the screen. For some large commercial data transfers (think server farm backups for big corporations), it is entirely unreasonable to use a portion of their bandwidth (the amount of data that can be transferred via a given internet connection, also referred to as the connection speed or maximum data transfer rate), to handle this. In fact, it’s often faster to load it onto hard drives and ship it by truck.

Given that the average consumer probably doesn’t have petabytes of data to transfer around, but most likely has a much slower internet connection (by probably at least an order of magnitude or five), we might still run into this problem. For example, the average download speed of an American household sits around 140 Mb/s (megabits per second) according to statistics from Speedtest.net, a popular internet speed testing site. Let’s calculate how long it should take the average American to download a 60 GB (gigabyte, note the uppercase “B”) computer game.

\[\frac{60\; \textrm{GB}}{140\; \textrm{Mb/s}} = \frac{60\; \textrm{GB} \cdot 8 \; \textrm{b/B} \cdot 1000 \; \textrm{Mb/Gb}}{140\; \textrm{Mb/s}} = 3429\; \textrm{s} \approx 57\; \textrm{min}\]So while that isn’t absolutely abysmal it sure isn’t exactly optimal. Realistically it would be even slower given time spent writing the game to your hard drive but for the sake of the argument we omit this. So at what point should we drive our home movie collection over to our cousins ourselves? Well, we can write up some Python code to find out!

Before we open our code editors, let’s start with the parameters of our model. Let’s say you average 30 mph on the first and final 5 miles of your journey due to local roads with lower speed limits. We can average any distance for the next 15 miles on either side to be moderate highway or country road driving at 50 mph, and the rest to be an interstate at 70 mph. This should account for how fast you really get to your cousin no matter how far away they live, and prevent the unrealistic case of driving across town at 70 mph. Now let’s write some Python code to express this time to transfer any arbitrary amount of data you can fit in your car as a function of distance to your destination. For the sake of the argument, we will assume that you have an absurdly large flash drive to give to your cousins.

# Time (in hours) to drive a given distance (in miles)

def time_to_drive(distance):

# If total distance is less than 10 miles, you average 30 mph

if(distance <= 10):

return distance/30

# For distances less than 40 miles, you average 50 mph for the middle miles

elif (distance <= 40):

return (10)/30 + (distance-10)/50

# For greater distances, we hit the interstate at 70mph

else:

return (10)/30 + (40-10)/50 + (distance-40)/70

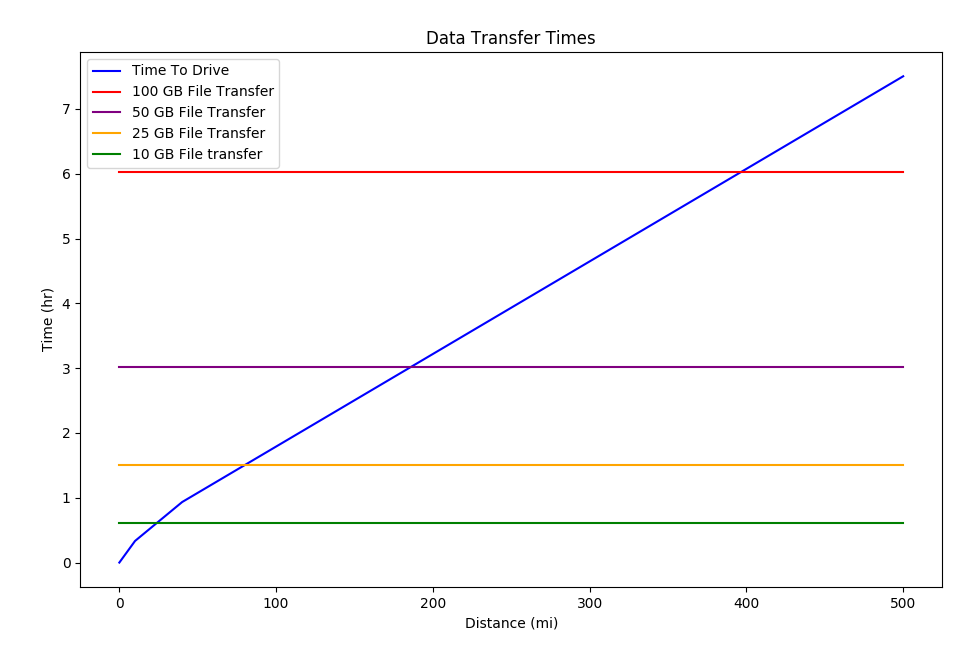

Now with the help of Matplotlib, we can plot this function. Let’s compare it to a given file transfer over an average internet connection, which we can take as constant with respect to distance, but varying with respect to size (the time it takes to send the signal from you to your cousins is probably less than a second, and more likely than not under something like 300 ms). We will assume you have to upload to a cloud service, like Google Drive or Dropbox first (at the average American upload speed of around 50 Mb/s, according to Speedtest.net), then download at the aforementioned 140 Gb/s.

So this is pretty clear evidence that if you need to send 100 GB of data to someone 350 miles away, it’s actually faster to drive it than to send it over the internet via a cloud storage service. Once we get to the order of a few terabytes, local mail and shipping companies even become viable. So there you have it: once you have to send your cousin a terabyte’s worth of home movies across state lines, just mail it.